Written by Didier CADIOU

When the 17000 tons Dutch passenger ship Nieuw Amsterdam left New York for Rotterdam in the Netherlands it had on board passengers originating from Germany, Austria, or Hungary. They are merchants, a lot of merchants, coming from America, but also from Latin America, they are musicians, farmers, engineers, merchant navy officers, stewards, bakers, students,.....Different social origins mix. But principally they are people, patriots, who wish to return to their countries. By the end of their journey Europe was fired up as after the declaration of the war between Austria-Hungary against Serbia (July 28), succeeded that of Germany against Russia (1st Aug), then Germany against France (3rd Aug), England against Germany (4th Aug), of France against Austria-Hungary (11th Aug), of England against Austria-Hungary (12th Aug)… Within a few weeks almost all the old continent is at war. As Spain, Scandinavia, Switzerland, and the Netherlands maintain their neutrality. And it is on this Dutch neutrality that the Nieuw Amsterdam passengers expect to reach their respective countries.

But in the Western English Channel, the battleship cruisers of the French 2nd light squadron watch. Their cruise was reinforced by some transatlantic ships hastily transformed into auxiliary cruisers. It is one of them, the Savoie, which intercepts the Nieuw Amsterdam on September 2, 1914, off the coast of Cherbourg. Suspected of transporting 400 Germans and 250 Austrians reservists [1], and 1000 tons of contraband goods, destined for the Central Empires, the Nieuw Amsterdam was diverted to Brest and arrived on the morning of September 3, escorted by the Savoie. Thus, the French Marine boarded a neutral ship, coming from a neutral country and going to a neutral country. Therefore, the Dutch government does not hesitate to protest against this diversion. To avoid such situations, the United States had questioned belligerent parties about their intentions towards neutrality. Beyond the Declaration of London in February 26, 1909, especially, treating about the concept of smuggling, the Decree of August 25, 1914 made it easier to the allies to intercept contraband destined to the neutral ports, which brought on American protests. This decree is finally abolished, and modified by the one of Nov 6, 1914 [2]. So the Nieuw Amsterdam was captured at a moment when the naval allies (France, Russia, England), were not really aware of the situation. But beside the legal problem, the French civilians, and military authorities had the problem of the confinement of these people who could not be considered as prisoners of war, as they had never carried weapons. In the beginning, from the 3rd to 23rd Sept 1914, these civilians were detained in the fortress in Crozon, and in Bouguen (Brest).

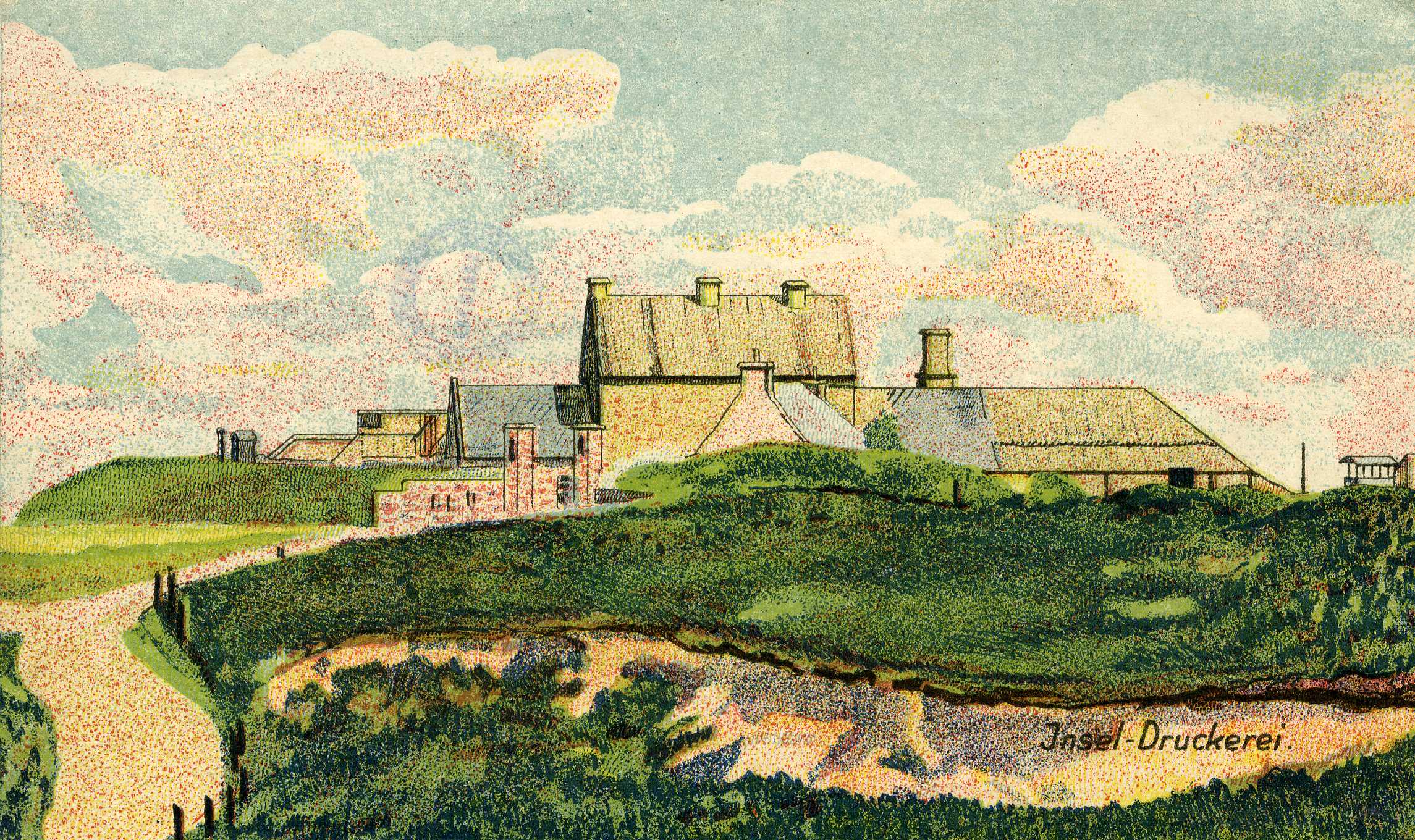

On Aug 17, the Ministry of Interior, already asked the Prefect of Finistère if there were any Islands, or Peninsulas that would be capable to eventually receive the foreigners, or suspicious evacuated individuals, or for prisoners of war. Immediately the Prefect proceeds with the inspection of the group of Islands, the Glénan, Ouessant, Sieck, Batz, and Ile Longue, of the Peninsula of Quélern… Aug 24, he hands in his report for the Bay of Brest. If the fortresses of Lanvéoc, Corbeau and Armorique, “which will be put out of service, not realizing the conditions of security and supervision necessary for the confinement”, he estimates nevertheless, that 800 men could be accommodated there, of which, 365 in Lanvéoc. Actually, it is Ile Longue that comes to the attention of the prefectorial authorities: “Ile longue seems to be the preferred place, because its isolation in the middle of the bay. In perfect security conditions, it would be easy to transform Ile Longue into a confinement camp by closing the narrow isthmus. The present fort to be disarmed would provide shelter for 430 men in the powder storage, old barracks, prison, ammunition hangar, housing, refectory, and bunkers, if one would sum up the plans available. The staff once installed, could help with the construction of barracks that could extend if needed, up to 5000 men. As for supplies, it would be assured not only through the harbor of Brest, but also by the Crozon peninsula with the possibility of using the resources of surrounding centers such as Châteaulin. The sick would be evacuated to Brest. It is conceivable that a camp of this kind might contain several thousand prisoners while allowing the reduction of the supervisory staff and the general maintenance costs. Its installation would be considered if a very high number of prisoners would be confined in Brest. Ile Longue contains stone quarries used for building paths. Prisoners may be employed in breaking stones ". What the report does not say, is that the isolation of the camp also helps keep prisoners safe from any violent reactions of the population as soon as the news from the front are known. In 1911 the census of Long Island shows that there were 139 people spread between Kernaléguen, Kermeur, the fort, and Bot Huelch. In 1914, some of them joined the army. The Prefect also contemplates the use of certain disarmed warships, particularly Carnot, and Charles Martel, which could each accommodate 1,000 men. In summary, by combining Ile Longue, the pontoons, the forts and barracks of Landerneau (1000 men), it is at 8800 prisoners that can be assessed the capacity of the area of Brest.

The fort of Ile Longue viewed from the camp

These figures are somewhat corrected in the following days. And September 13, the Prefect gives a list of possible places of internment in Finistère to the War Department : chateau du Taureau (100 men), fort of Lanvéoc (350), fort of Armorica (500), fort of Ile Longue (430), Ile de Sieck (400), Carnot (1000), Charles Martel (1000), and the camp of Ile Longue (4-5000) after the construction of barracks. . The same day, he informs the Ministry of Interior that some places could be available within five days: fort of Crozon (570 men), battery of Landaoudec (100), battery of Lanvéoc (100 women or men), battery of Armorique (100 women or men), and Ile de Sieck (400 men). The decision was made, and four centers of incarceration were settled in the peninsula of Crozon: Crozon, Lanvéoc, Landaoudec and Ile Longue, plus the pontoons, and to a lesser extent, Ile Trébéron.

Thus, a commission goes to Ile Longue to assess the compensation to be paid to the owners of the land necessary to build a camp for prisoners of war. For the camp, 140 plots are involved, for a total area of 7 ha 49 a 22 ca plus the military land of the fort and external batteries. The temporary occupation of the land begins September 29, 1914. “You get to this camp: on one hand by sea, using a prepared landing on a rocky point, north of the camp and west of the island, originally built of gravel on the side of the cliff and leading to the camp entrance, and, on the other hand, by land via a gravel carriage road, crossing the island from north to south and connecting it to the peninsula of Crozon” (descriptive state of the site of August 24, 1916).

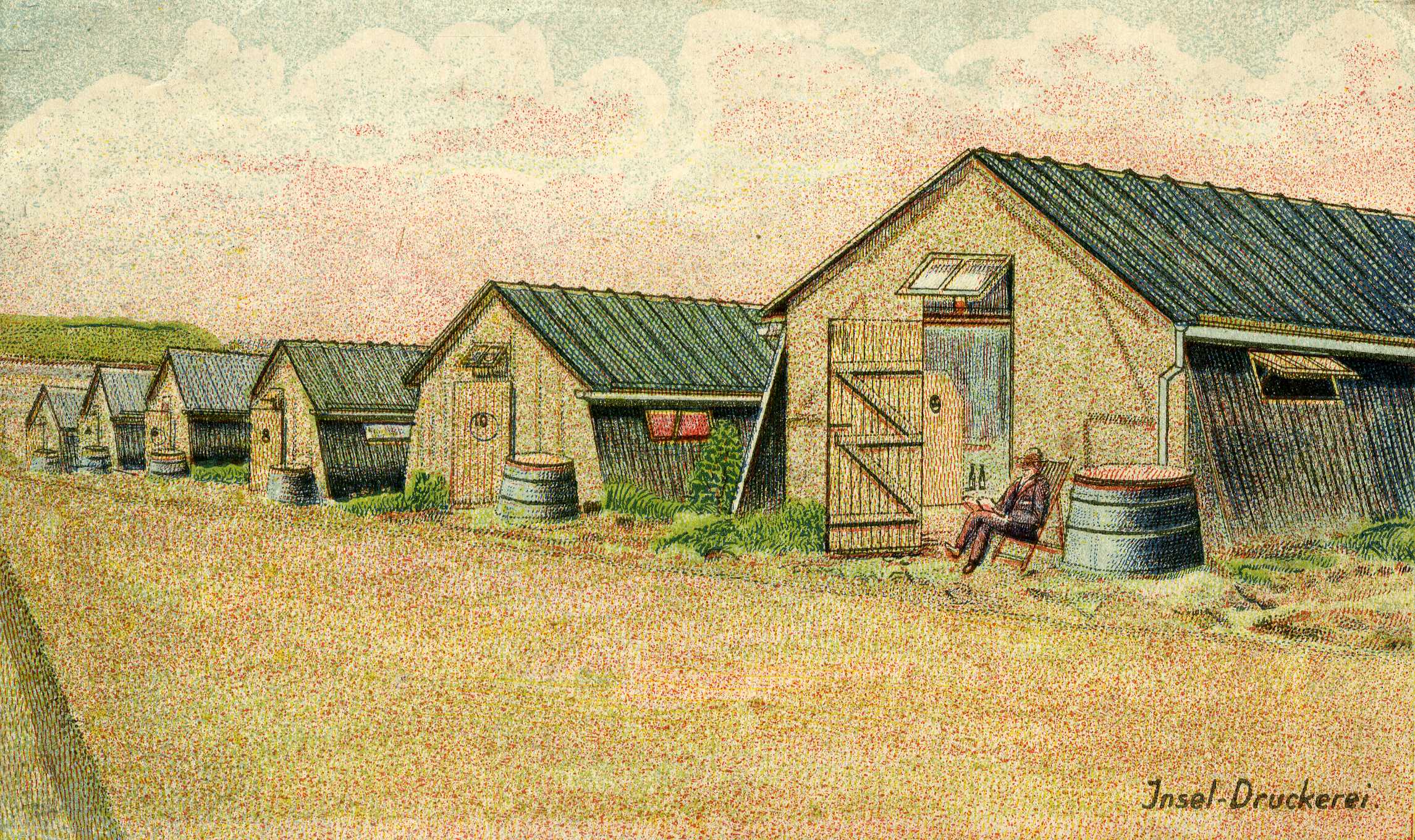

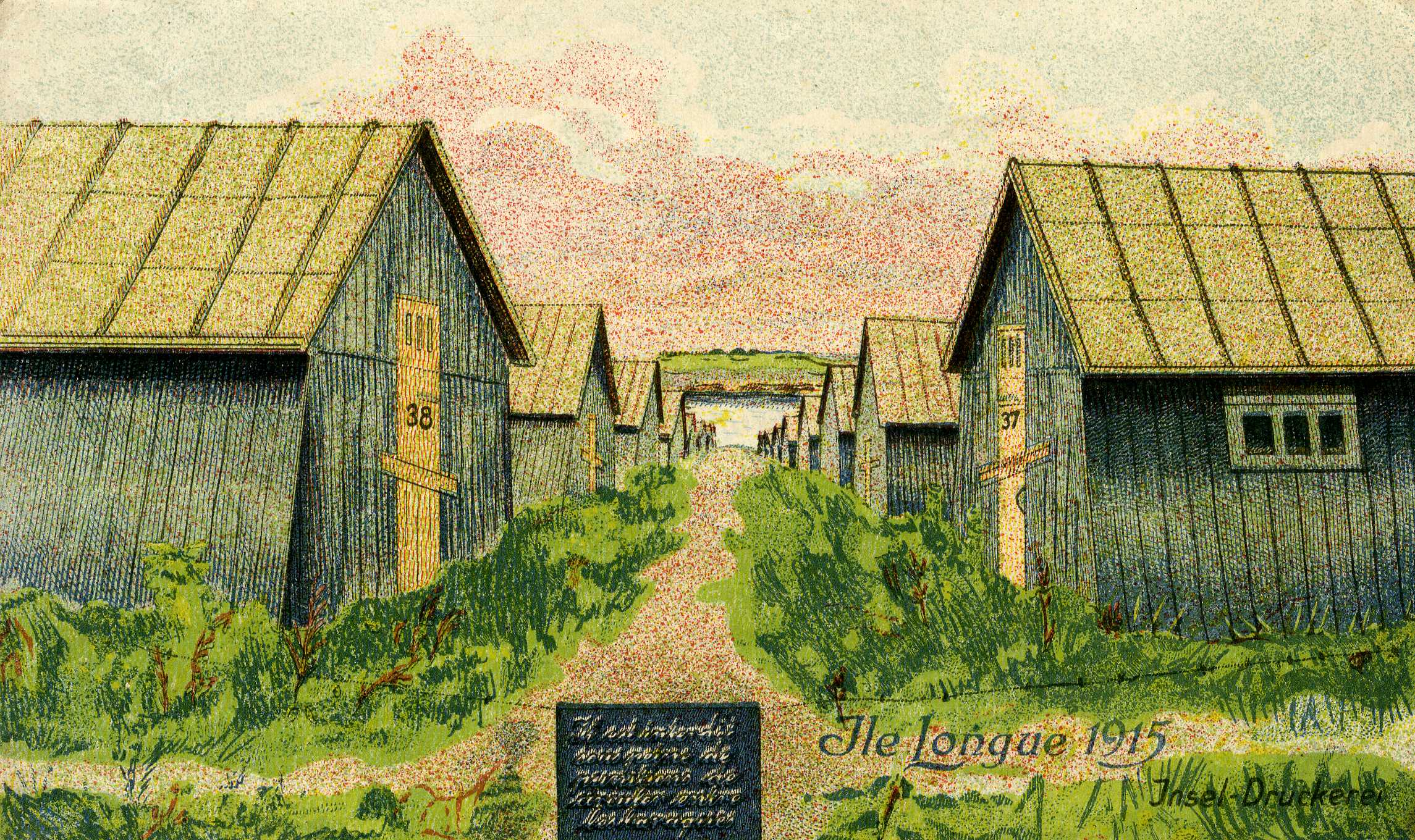

Military engineers run the building of 60 military engineer model (24 x 5.70 m) barracks, each accommodating 40 men, 8 Adrian barracks with cemented floor, each accommodating 60 men, 10 barracks for kitchen use (32 x 6, 10 m), 12 barracks for washbasins (8.50 x 3.25 m), a barrack for showering (17.70 x 4.15 m), 3 covered sheds for washing and drying clothes (17.65 x 4 m), 3 groups of 17 toilets in each compartment, a barrack for an office (12.25 x 6.60 m), a model of military engineer barrack to be used as a guardroom, a large barrack for a canteen (50 x 8m), and a barrack to be used as a barn and shed (40 x 5.45). The barracks of the camp are surrounded by a 2 meters width barbed wire fence, and a walkway. To the west, adjoining the camp, a sports area including a race track, a football field, two tennis courts, a field for athletics and bowls, is also built and enclosed by barbed wire. Outside the enclosure, the camp also occupies a small barrack and shed as the officers’ mess, (5.30 x 5.70 m), the premises of the fort, and a barrack in the moat (18.20 x 5.80 m) for an infirmary, and 5 of the 6 “shelters” of the external disused batteries, used for disciplinary premises or storage. The guards still occupy a group of barracks to the west of the camp itself.

The water supply is a real problem, initially, it is necessary to bring drinking water in barrels. It is also thought to use a source close to the camp, but the bacteriological analysis of January 17 1915, shows that it is not drinkable. The project is then to collect drinking water from Saint Fiacre using two motor pumps (Faivre system) installed in a shed (6.10 x 4.57 m) and to pump it to the water tower of the camp by a pipe of about 4 kilometers. Every day, a corporal and a prisoner are in charge of the operation of these pumps. As for the non-drinking water, it comes from the roof, and from a nearby source (using a Japy pump) which supplies three tanks. A second water tower, for washing and showering, is powered by another source using also a Japy pump.

Meanwhile, on September 23, most passengers of New Amsterdam were transferred to the old battleship Charles Martel anchored in the harbor. Some, which had reported their rank in the army, often cadet officers, are locked up, according to what they said, in the “château d’Anne de Bretagne” in Brest. Prisoners from the pontoon then joined the camp of Ile Longue, mostly between November 5 and 24. The first to arrive were probably involved in the construction of barracks for their following comrades. It seems that the passengers of the Nieuw Amsterdam were the first to reach the brand new internment camp. They were soon joined by nineteen German, Austrian and Ottomans, captured on November 6 in the western English Channel, aboard the Dutch liner Tubantia by the battleship-cruiser Kleber (2ème Escadre légère, Brest). With a crew of 293 men and women and 486 passengers, this ship had left Amsterdam and, after a stopover in Folkestone, was on his way to Buenos Aires, via La Coruna, Lisbon, Santos and Montevideo. The commander of the Couédic is unable to investigate thoroughly and must let the steamer go, while having “reason to believe that there were Germans having Brazilian, Argentine or Chilean documents” on board the Tubantia . His prisoners are incarcerated initially on Charles Martel, then, transferred to Ile Longue on November 21.

Unlike the camps of Crozon and Lanvéoc, which are civilian prisoners camps, managed accordingly by the Ministry of Interior and the Prefect who is its departmental representative, the internment camp of Ile Longue is a POW camp run by the Ministry of War, and whose guard is provided by the 87 Territorial Regiment. So there are infantry, cavalry, artillery soldiers... captured on the front. But, and this is a peculiarity of Ile Longue, there are also civilian prisoners. Cohabitation seems to go well : “Among the civilian people, the”Hungarians“disciplined and industrious peasants have always provided the amount of work required of them ... only the German civilian team did not give the performance it was capable of” written on March 15, 1916.

The alignment of barracks for the internees, north of the camp.

Under the command of Squadron Leader Alleau, regulation of the camp does not leave much room for personal initiative, as shown by the schedule in effect. All packages received are searched. They all contain tobacco, tin cans, biscuits, coffee, tea, chocolate, sugar, half of the time some soup tablets, cold cuts sometimes, and not so often underwear or clothing : “In summary, a little of everything in each package, but in very small quantities. Dessert will replace the substantial meal”. Camp administrators also note that, after June 15, 1916, it “is interesting to note ... the decreasing progression ... which seems to answer to an order, of the number of packages shipped from Germany.” Concerning the meals, a ministerial message received January 26, 1916 states that “the food of German prisoners held inside the camps would be exactly the same as that which is distributed in Germany to French prisoners in the same situation.” ... Three times a week, these prisoners receive 120 grams of meat, plus once a sausage, for a total of 460 grams. Only 300 grams of bread is allocated to them per day ... This measure does not apply to the sick or injured, but, it must be strictly observed concerning all German prisoners remaining within the camps, either they are waiting for a future occupation or that the work that they occupy does not require any physical effort. On the other hand, the decrease of the rations of meat and bread will be compensated with an increase of the quantity of the other food (for example beans, potatoes, etc.) representing an equivalent nutritional value“. Swimming in the sea is also subject to regulations from May 20, 1916, and if”these are not compulsory swimming ... it is in the interest of all to participate." A boat, equipped by an officer, two rowers and two prisoners that are very good swimmers, has to insure the safety of this collective swim. Besides sea swimming, prisoners can take showers, but in period of drought their use is limited to Saturdays weekly, from 1 pm till 5:30 pm.

DAILY SCHEDULE

(According to a memo of march 16, 1916)

06 h 00: Wake-up

06 h 00: Call

06 h 30: Coffee

06 h 45: Gathering of the workers

10 h 00: Return of the workers

10 h 30: Lunch

12 h 30: Assembly of the workers

17 h 30: Dinner

18 h 15: Mail distribution

18 h 30: Closing of the canteen

19 h 00: Entering into the barracks

19 h 15: Call

The camp does not live totally in isolation and prisoners can communicate by mail (restricted however) with the outside. The United States embassy helps the prisoners most in need (December 1915). A committee of two Swiss doctors and a French doctor also goes to the camp to examine the likely prisoners, because of their wounds or of their infirmities, to be interned in Switzerland. The International Red Cross and the Christian Union of Young People also maintain contact with prisoners. In March 1916, the representative of the last, M David, of Geneva, becomes the speaker on behalf of the prisoners and asks that a free barrack be put at their disposal to serve as a library, recreation, and a study room . In July, 1916 he himself goes to the camp. A few months later, prisoners request the use of six Adrian barracks to serve as rooms for meeting, photography, gymnastics, music, study, and a library. Some, started a theater group, and archives, still today preserve 27 decorated artistic notebooks.

Clashes however occur. So on January 28th, 1916, the commander Alleau notes that “abusing the favor which had been granted to them to draft a camp newspaper, prisoners took as a pretext, a question of distribution of bread to write, in an article of the last edition of the newspaper in question, a criticism with a spirit of indiscipline and proud arrogance asserted well on the way the French people understand the humanity and incite the hatred for the German prisoners”. Consequently, the camp newspaper is forbidden and the printing material seized, the author of the article and the printer of the newspaper imprisoned, the theatrical representations forbidden, as well as students meetings. From April 8, 1917 however, a weekly newspaper, “Die Insel Woche” (the Week of the Island), reappears, and until January 5, 1918, 51 numbers were published.

In his report of May 23, 1916, the first class military intendant Blaise, notes that it “exists in Brest, in Ile Longue, a prison camp which was originally planned to receive 5000 men. Following diverse modifications, this camp still counts to this day approximately 3900 people. But at its highest level, the number of prisoners of Ile longue hardly exceeded 2000. Today it varies from 1400 to 1500. Also, the Vice – Admiral, the maritime Prefect declared recently to the general Inspector of the 2nd district, that the navy could not assure the food of no more than 2000 people because of the conditions of navigation around the island. It would thus be enough to leave in the camp the necessary number of barracks to accommodate a similar number of people. The rest of the barracks can be considered as available and receive another assignment”. From June 18th, nineteen available barracks at Ile Longue are put at the disposal of the service of the Estate management. On July 9th, the intention is to take seven Adrian barracks to transfer them to the instruction centers of Lanilis, Blain, Varades, Fontenay-le-Comte and Sables d’Olonne. Their dismantling must be assured by the war prisoners.

But the same day, a message indicates that, “the Department of Interior takes the responsibility of all the civil war prisoners that are presently depending from the War Ministry. These civil war prisoners will be accommodated in the buildings of the camp of Ile Longue, situated in the South of the natural harbor of Brest. Consequently, 300 military war prisoners of this camp will be sent to Quiberon Penthièvre, and the rest to Brest Kéroriou... The barracks will be cleaned, and disinfected, by the civilian prisoners still on Ile longue”. Also an order was given to reconstruct the two barracks that had been demolished.

It is planned that the camp of Ile Longue receives the civilian prisoners from the camps of Aurillac and Uzés, the move should be finished by July 26. In reality, the 100 prisoners from Aurillac only arrive in Ile Longue, via Brest on August 19,, followed by 605 prisoners from Uzés on August 22. Amongst the new arrivals, a certain number were captured on board of commercial ships, many were taken prisoners in Cameroon, Togo, Morocco, Algeria, Belgian Congo, and some captured by the Belgian, or British troops. They are now added to the 1776 civilian prisoners of the camp, 8 of which are in hospital, 2 in prison, and 6 working outside.

Since August 16, the camp is under the direction of the Ministry of Interior. New civilian staff arrives to replace the military to insure the administration of the camp, and a camp master, a book-keeper, a supervisor and ten guards were assigned to Ile Longue. Only the sergeant major Mauroux keeps his position as chief depot assistant. The prisoners also carry out different administration tasks (interpreters, secretaries,)…In the sub prefecture of Brest, it is also necessary to recruit two typists-book-keepers, a food and postal parcel handler, a supply controller, an errand boy, as well as in the prefecture where two extra employees are assigned for correspondence, reports, and censoring… A group of four to six soldiers are also made available by the military authorities to load the food destined for the camp every morning, at the bridge Gueydon in Brest. Transport is then carried out by a launch towed by a gunboat, which assures the service between the Arsenal and Le Fret. Additional help is given once a week on Thursdays, for the embarkation of postal parcels.

For its part, the 87th Territorial continues to maintain general supervision of the camp. But north and east of the country, the front consumes and asks more and more human flesh. On September 11 1917, the Headquarters therefore attempts to recover a hundred men, “recuperation which presents a sense of urgency”. After a war of position (symbolized by the battle of Verdun), from spring 1917, the Allies launched indeed a bloody and unsuccessful offensive at the Chemin des Dames in Arras, Flanders, ... The size of the 87th Territorial decreases, from 333 men on August 16, 1916, to, 230 in December 27, 1916, 170 on February 17, 1917, 162 on November 26, 1917, and 130 on February 17 1918. In return, modifications are undertaken to facilitate the monitoring of the camp. A second fence, and acetylene lighting are installed on the outskirts of the camp, and the present infirmary, until now in the fort, is transferred September 1917, to one of the available Adrian barracks.

Also, the prisoners themselves suffer the consequences of this economy of personnel. Then, in 1915, the committee of help of the camp obtains permission to organize a small semi-religious ceremony on the evening of December 24, "followed by a distribution of gifts under the Christmas tree” (consisting of foodstuffs, candy, tobacco and clothing, for the needy of the camp), this favor is refused by the Sub-prefect of Brest in 1917 because the effective of the garrison is not sufficient to insure its surveillance. Indeed, the previous Christmas Eve a Hungarian internee, took this opportunity to escape, before being recaptured the next day by the police force of Argol.

Soon, there is a shortage of oil for lighting and for the stoves that is felt in the camp. An attempt to replace the oil stoves by charcoal stoves is made. The sale of food in canteens is soon stopped. “In short, internees of Iles Longue suffer the re-strictions that are imposed on the entire civilian population but at a lesser extent.” Even the wood to repair barracks runs out. Some internees complained to the United States embassy; because of the bad conditions of the roofs, rain enters the barracks. By the way, the Embassy delegate can notice it by himself on September 1916. On November 20, a report also indicates that 800 rolls of asphalted cardboard necessary to repair the roofs have become insufficient because of the recent storms that caused extensive damage to the roofs of the buildings. Another 700 would be needed. On January 3, 1917, the prefect of Finistère must also insist, to the Director of Engineering of Nantes to obtain “10,000 meters” whose delivery seems to be subject to the supply of wagons: “the delay in the delivery prevents the achievement of work recognized indispensable, and whose non execution recorded since long months by the United States Embassy will bring reprisals. In presence of this responsibility, I again insist that delivery be made extremely urgently.” A telegram full of hidden meanings, written at the same time as the US President Wilson was working for peace, before finally declaring war to Germany on April 6, 1917. The repairs are completed by the end of the month of January 1917. Some prisoners also had the opportunity to see the first 5 American transport ships escorted by 12 destroyers and an armored Cruiser, entering into the Brest Harbor on Monday, June 25, 1917. According to La Dépêche de Brest of July 1, these prisoners were dismayed by the early arrival of the Americans, without any attempted attack by a submarine.

And then, sometimes, there are unfortunate incidents like on September 13, 1917 when the head of the camp reported that bullets (at least three) coming from the armored cruiser Montcalm (but in fact from the cruiser Dupetit-Thouars), anchored in the bay of Le Fret, were fired into the camp. There were however no injuries or damages. The warrant officer, commanding the detachment of guards, immediately went on board the ship where some measures were taken to prevent the recurrence of such events.

Rapidly the prisoners were asked to participate to various jobs usually done by military. Thus, some are employed to build barracks in Portsall, Ploudarmézeau, Quélern, Saint Renand ... or to build a TB sanatorium for the military personnel at Guervénan in Plougonven. In May 1915, the War Department had also decided that prisoners of war and military manpower could be made available to the administra-tion of Water and Forests, municipalities or private individuals which exploit logging. Faced with a shortage of labor, the civilians in fact claim these prisoners for farm work - several civilian internees of Ile Longue, thus, reach the departments of Eure and Allier - but also for the construction of the railway Châteaulin-Camaret and local roads, for exploitation of quarries, for chemical plants, canneries, paper mills, grains mills, and tanneries… The camp itself employs prisoners. Thus, September 6, 1916, 132 prisoners work permanently in the kitchens or workshops (carpenters, tailors ...) of the camp, for a daily wage of 0.30 francs. Others are employed in administrative tasks. Their salary allows them to purchase extra things, like butter, marmalade, flour, sugar, fresh and dried vegetables, chocolates, biscuits, tobacco, oil, newspapers ... at least when there is no shortage. Since August 1916, internees may indeed receive the press, particularly La Dépèche de Brest, but also various other newspapers, magazines such as: Le Matin, L’Humanité, La Victoire, Le Figaro, L’Illustration, Le Petit Journal Illustré, the Daily Mail, Frou-Frou, Fantasio ... and some war atlases.

For its part, in all its strictness, the administration has estimated the costs of running the camp, whose expenses consist primarily of food, shoe repairs, upkeep of clothing (or purchase for the most needy), coal and firewood, oil, pharmaceuticals and the care of four horses. It should be noted that the personal costs do not seem to be taken into account. In 1916, for an average of 1,800 internees, the monthly costs of the camp amounted to 49,589 francs during the summer (or F 0.918 per day and per internee) and 54,517 francs in winter (or F 1.009 per day and per internee).

The alignment of the internees barracks, east of the camp.

Relieved on the eastern front by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Russia (March 3, 1918), the Germans attempted a last offensive before the massive arrival of U.S. troops on the French front. In May, the breakthrough at the Chemin des Dames allows German troops to reach the Marne again. Foch then launched the second battle of the Marne and the assailants were forced to retreat to the Siegfried Line (September 15, 1918), then to the Meuse. The German government has no choice than to make an offer of armistice to the United States, on the night of October 3 to 4. The German fleet of Wilhelmshaven rebels on October 29, while the revolution broke out in Vienna on October 21, in Munich on November 7, in Berlin on November 9, ... Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicates the same day, before going into exile to the Netherlands the next day. The German delegates finally sign the armistice in Rethondes, and on November 11, 1918, at eleven o’clock, the bugle can finally sound the “cease-fire” that the survivors have been waiting for more than four years. Other armistices preceded: with Bulgaria on September 30, the Ottoman Empire on October 30, and the former Austro-Hungarian Empire on November 3. More than 8.5 million men lost their lives in this conflict …

But if the guns are silent on the front, the internees still have to wait to be released. Transfers of prisoners continue nevertheless, and from November 12, 150 internees were sent to the camp of Vire (Calvados). A hope of release, however, had been given to some of them following the Germano-Belgian Convention of Bern (March 22, 1918) for the repatriation of civilian internees. But on August 30, 1918, the Sub-Prefect of Brest is informed that the French Government decided to suspend any repatriation of German civilians interned in France. On October 16, the help Committee of the German civilian internees of Ile Longue (Ile Longue Deutscher Hilfsausschluss) is authorized to send 19 crates to the Swiss Delegation in Paris to be forwarded later on to the Red Cross in Frankfurt. The inventory of the crates reveals an important intellectual and cultural activity at the camp showing, works of scientific, legal, naturalists, Literature, graphic, Arab and Turkish studies, artistic drawings, watercolor paintings, and various art objects...

Gradually, however, the camps are closed (as Crozon January 8, 1919) and many prisoners are transferred to Ile Longue. Thus, on 26 August 1919, 140 Austrians and Hungarians arrive from the camps of Luzon, Noirmoutier and Ile d’Yeu in Vendée. Following this transfer, the camp commander informs the Sub-Prefect of the “low spirit that exists in the camp of Ile Longue” since their arrival. Already, on May 2, he had to report that “some red flags were displayed on almost all the barracks of the internees on the occasion of May 1st”. “Immediately, the group leaders were assembled and an order was given to have these flags removed, while making them understand the unlawfulness of the display of flags that could bring disciplinary action ... All flags were removed, except a black one flying over the barrack No. 1. This cloth carries the inscriptions: May 1 - Long Live the international - Long live the social revolution - Liberty and welfare to the people – Death to the villains ... Confronted by this event, the lieutenant commanding the company put himself at our disposal. There was no reason to intervene, as no further incidents had occurred.” An Austrian and a Hungarian who had hoisted the black flag were recognized, and punished by five days of prison. Is this incident a remote consequence of the Spartakist revolt in Berlin (January 1919), or, is it simply a demonstration of the impatience of the internees waiting for their release? Also, escapes are increasing in the camp, like during the night of May 10 to 11, when two internees managed to escape in order to reach the U.S. camp of Pontanézen where they hoped to get on a train heading to Germany. They are stopped near the camp by the American military. The increase of these escapes brings the Sub-Prefect to request the repair of the barbed wire fencing surrounding the camp and the clearing of the bushes that enable the internees to hide themselves and to be out of sight of the sentries (August 22, 1919).

But, the French government seems unwilling to release its prisoners until peace is signed, and it was only done in Versailles on June 28, 1919. On May 15, 1919, however, a convoy of 616 Austrian and Hungarian civilian internees left the camp for their repatriation. Amongst them were 106 internees captured from the Nieuw Amsterdam. Peace with Hungary was only signed on June 4, 1919 (Treaty of Trianon), and with Austria (Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye) on September 10, 1919. The treaties of Neuilly, with Bulgaria, and Sevres with Turkey, followed respectively, on November 27, 1919 and August 10, 1920.

On October 14, 1919, the Minister of Interior informs the Prefects that, “following the examination of the peace treaty by Parliament, the Government has decided to release by a general decision, all subjects of enemy nations, still retained in concentration camps ... Therefore, there should no longer remain any prisoners in the internment camps, other than some individuals who are considered doubtful, or undergoing lawsuits.” The clauses of the Treaty of Versailles provided for plebiscites in some parts of Germany, especially in Saarland and Schleswig. The camp administration was therefore required to identify by name the 18 interned Germans of the Saar Basin who wished to be repatriated to this area (August 6, 1919). As for the 14 Schleswig subjects, they were astonished on August 27, 1919, “to be still forced to endure the interminable captivity especially since the clauses specifically concerning their country, had given them a glimmer of hope... ”

At last, the convoys of October 20th, from Brest to Mainz, and of October 30th, 1919 of Brest to Wissenbourg, return home 1068 German internees, among whom 435 prisoners from the Nieuw Amsterdam. “Because of the very small number of internees left in the camp”, the state employees of the camp are then informed that they “will cease their functions the following Saturday, November 15”, with the exception however of four who have to stay because the date of dissolution of the camp still remains uncertain. Brest suppliers, who are more reluctant to work for such small quantities, are also replaced by locals. There are still some escapes as on the night of November 26 to 27 when two internees escaped, followed by two others on December 2 who were however caught in Châteaulin. The camp of the civilian internees of Ile Longue is permanently closed on December 31, 1919.

A few days later, January 7, 1920, a report orders that the premises and equipment be returned to the military authorities. The general situation is the same as in 1916, except that a barrack used as an infirmary near the fort was moved inside, and north of the camp. Given their age, buildings and furniture are in the condition they were in 1916. The statement prepared February 20, 1920 for the settlement of accounts allows to estimate at 22 the number of deaths that occurred in the camp, and 13 the number of successful escapes.

The last camp barracks were sold by public auction July 17, 1920, the bedding material and clothing effects followed September 6 and 7, as well as tool equipment September 10. Some of these barracks were bought and rebuilt in the passage of the Fret by ship builders, as Geoges Stipon that established himself between the road and the pond in 1922. Today, they are known as “American barracks of Ile Longue”. On May 10, 1920, the City Council, that had been entangled for a long time, with its problem of water supply for the town of Crozon, had also agreed to the purchase of pumps, pipes and tanks for a sum of 11,700 francs. All of which is intended for Yunnic to supply the village, but the installation is not done [3]. It remained to the administration to return the land to their owners and to compensate them. The task was important because the soil had been profoundly damaged (paved road, landscaping ...) and the boundary posts had disappeared.

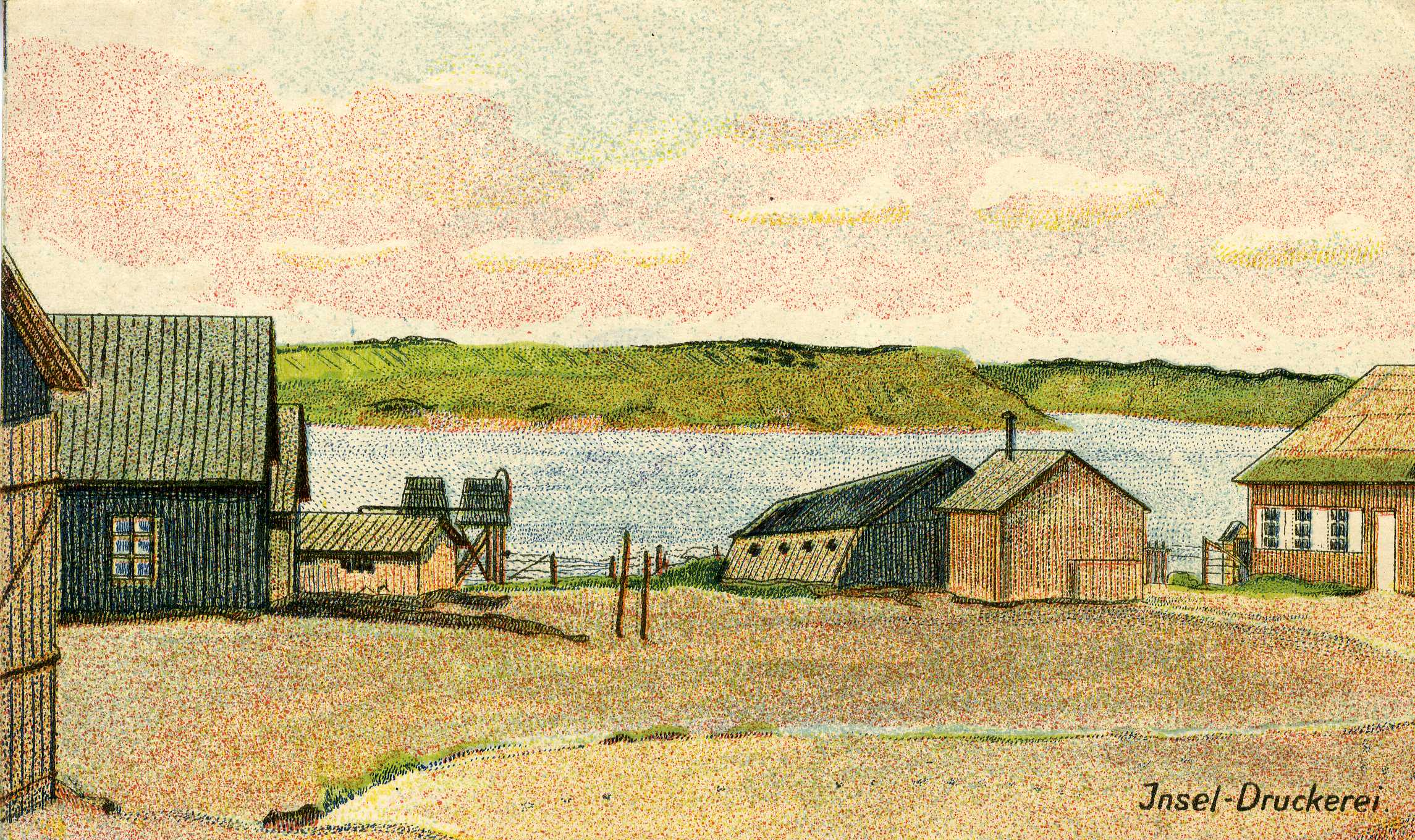

Entrance of the camp. Visible on this drawing, from right to left, the offices, the guards house, the showers (with their water tanks), and the canteen.

The history of this camp has left altogether rather little traces in the memory and even less on the ground, since its location is now the Operational Base of the Strategic Oceanic Force (la base opérationnelle de l’Ile Longue, force océanique stratégique).

In September 1944 by a curious turn of history, it is in Rostellec, at the entrance to Ile Longue, that the occupying German forces established their prisoners of war camp, the Front Stalag # 284. After evacuating the population, there, they installed the British airmen and especially the U.S. military captured during the fighting of Festung Brest. There were also French prisoners, of African or North African origins, and about fifteen underground fighters of the Compagnie Bretagne (later known as Bataillon Rene Caro) captured in Brasparts and Tréhoux on August 16. The camp was enclosed by barbed wire, with the exception of the shore which remained free access. The guarding was assured by older soldiers who offered little resistance during the liberation. The German headquarters had been installed at the entrance of the village in a large house called Ker Colette, and white sheets marked out the camp for Allied airmen. While Americans played ball, the French prisoners were involved in chores: installation of barbed wire, recovery of corpses on the shore, the duty of carrying water from St. Fiacre by means of a tank pulled by a horse...

Some escapes occurred as that of Joseph Boennec who, on September 13, managed to reach Beg ar Zorn to embark on a small boat going to the coast of Plougastel. In total, close to 400 people were interned in Rostellec before the camp was liberated Sept. 18, 1944, around 11:00 am, by the 2d U.S. Ranger Battalion, and some fighters of the resistance [4]

. Not far away, Le Fret had been transformed into a vast sanitary zone, where, many war-wounded were transferred.

Sources

The present article was drafted from documents kept in the Department of Archives of Finistère and particularly the bundles 9 R 2, 9 R 7,9 R 8, 9 R 8bis, 9 R 8ter, 9 R 33, 9 R 45, 9 R 76, 9 R 90 - 100, 9 R 114. Our documentation was completed by the reading of La Dépêche de Brest of September 3rd and 5th, 1914 and of July 1st, 1917 deposited to the municipal Archives of Brest (1 Mi 60 and 1 Mi 69).

Few authors evoked this prison camp in their writings. Let us quote however, François Menez, “Brest pendant la Guerre”. La revue Maritime, N 187, July, 1935, page 27; François Menez, “De Morgat au fort de Crozon”. La Dépêche de Brest, February 8th, 1939, (municipal Archives of Brest, 1 Mi 158); Georges-Michel Thomas, « Flashes sur le XXe siècle » La Presqu’île de Crozon. Histoire, Art, Nature, Nouvelle Librairie de France, Paris, 1975, pages. 282 - 284; Auguste Dizerbo, Notes et Documents sur l’Ile Longue et son Histoire, s 1; March, 1987, 6 pages and appendices.

The iconography of this article comes from the departmental archives of Finistère (bundle 9 R 7).

Notes

(1). These figures are given by La Dépêche de Brest of September 5th, 1914 (municipal Archives of Brest, 1 Mi 60). But, Louis Guichard and François Menez spoke of 750 passengers, German or Austrian. It was also known, that amongst them there were most probably Hungarians, counted as Austrians.

(2). L. Guichard, Histoire du blocus Naval (1914 – 1918), Payot, Paris, 1929, 240 pages.

(3) P. Graveran, “Histoire d’eau à Crozon”, La Presqu’île de Crozon, bulletin paroissial, Crozon, 1976, pages 5 - 26.

(4). Information obtained by Resistance fighters interned in Rostellec: Mr. Yves Castel, François Le Lann, Joseph Boennec.